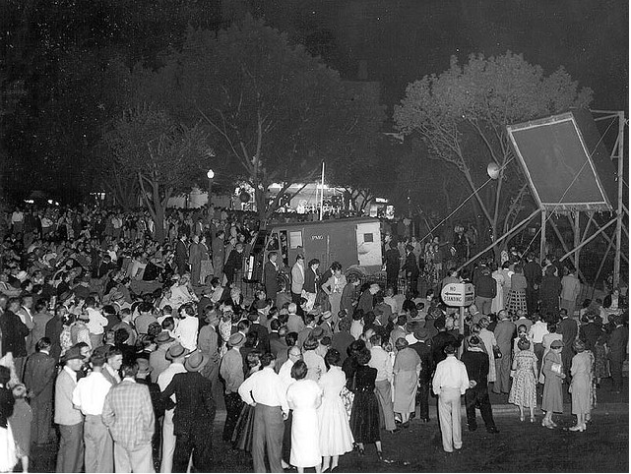

Crowd Watching Television at night in Fitzroy Gardens at Kings Cross on New Years Eve, 1955-56 (ABC Reference ID: abc.net.au/photo/DP000092)

Archives simply put are collections of objects or information that is recorded for a later time. This has been an ongoing tradition for centuries, technologically progressing. Some archives are open for public use (creative commons) like the ABC photo above, pulled from their media archives available on the net.

Our obsessive humanistic desire to archive our life and experiences can be categorised under ‘archive fever’ (a term coined by and the name of Jacques Derrida’s 1995 publication). The dynamic relationship between the theory behind archives and the practical collection of materials creating an archive is constant, but how do these theories and models enter their practical development and use in media? Different models will lead to different outcomes based on the techniques they employ to conjure memories (our own personal archives) and connections, perspectives, perceptions and possible future actions. It is the method of communication used that affects how we process these connections. This mediation of what happened (in theory) to real life interpretation results in our understanding. By this logic, anything we process- stories, pictures, articles- must be processed through theories entrenched in us about how we perceive the world to work, thereby generating our opinions on the archived materials that mean something to us. This relationship, a network between elements and actants is described in Latour’s Actor Network Theory (ANT).

It is interesting that two people could have such a different perception of the photo shown above, based off the connections they associate with it because of the filters their perceptions go through first shaped by theory. It is also interesting that whatever mediation we use to express ourselves are experiences we are carrying on in a different for. For example, showing someone a picture of watching TV in a crowd is not the same as being among them on that particular night.

This creation of archives can also be seen from the point of view and human and non-human interactions, whereby we interact with inanimate objects but the meaning that they possess is understood by us and therefore necessary to record. Because we feel like we must have a reliable record of the past, archives also compete with each other to be the most complete and comprehensive source. Whether through the archive’s organisational structure or its content, a great deal of power is attached to this data ownership because of its ability to distribute content with ease; archives also demand authority as a trusted source.